The Archive as Mirror

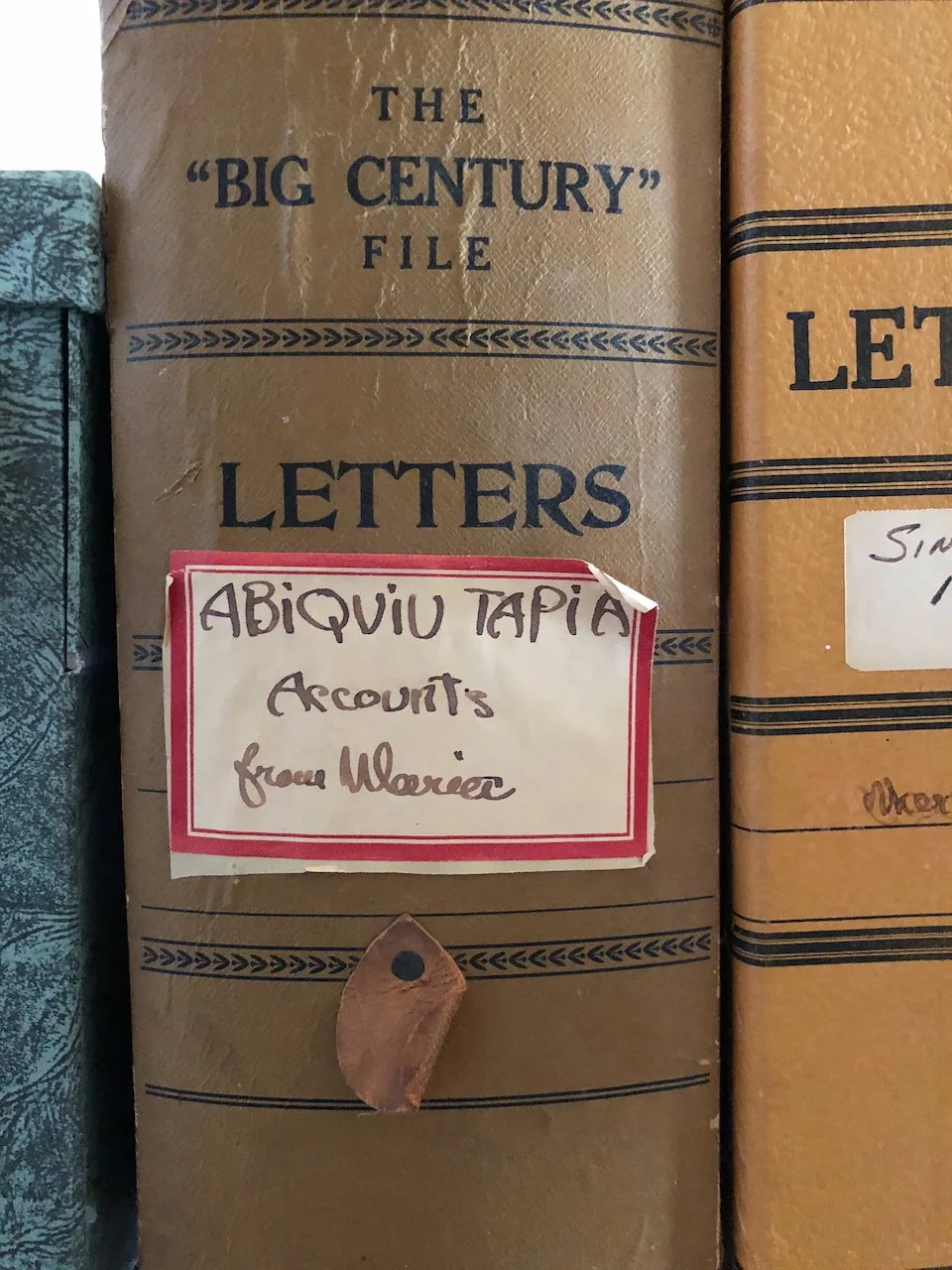

A selection of books at Taliesin West. Wright and O’Keeffe shared many interests reflected in their book collections, including Japanese art.

On TV and in books, archival research always feels glamorous, romantic, and a little dangerous. There are secrets lurking conveniently at the top of a thick pile of folders, some arcane illuminati conspiracy ready to be unearthed by a precocious grad student who may also be a witch and/or vampire. The reality is considerably less enthralling. Archives are routinely colder than you’d prefer and someone is likely watching to make sure you’re wearing your gloves.

But every archive does have a personality. Getting to know the quirks and nuances of the file structure, the institutional memory, and the decidedly human archivists is critical to the process, the thing that may occasionally lead you to a new discovery. In researching Through the Long Desert, I became very familiar with the Georgia O’Keeffe and Frank Lloyd Wright archives.

Ms. O’Keeffe’s archive is divided between the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center in Santa Fe and the Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscripts Library at Yale. Wright’s things are a bit more dispersed. All of Wright’s letters and drawings are at the Avery Library at Columbia University and the models. There’s a trove of digital assets managed by the team at Taliesin West, and various personal effects show up at there, at Taliesin in Wisconsin, and at the Oak Park house in Chicago. Some of their archives also remain in situ; a lot of furniture and art is in its original spots at Wright’s homes and at O’Keeffe’s. Though the word archive conjures up the image of an orderly collection of letters and manuscripts tucked away in a climate-controlled university, the archive of a life is rarely so simple. For both Wright and O’Keeffe, it’s the paper and microfiche at Columbia and Yale, but there’s the work itself (the paintings and buildings), their clothes, other belongings,

To a large extent, the archives are reflections of the people whose lives they are intended to preserve. O’Keeffe, for the most part, was meticulously organized (or paid other people to be on her behalf). She kept most of her receipts, organized her book collection by topic, and kept many of her collections in labeled boxes. She was diligent about curating her legacy while she was alive. She was also, crucially, financially stable from the 1920s on. Wright, by contrast, operated in tandem with a coterie of apprentices and fellows, a massive workshop-style operation that divided time between Taliesin and Taliesin West. At various points, he had offices in Chicago, Tokyo, and Los Angeles. Taliesin burned in 1914 and again (less disastrously) in 1925. Wright was perpetually in debt or on the brink of it, selling off assets like his collection of Japanese prints to achieve temporary solvency at various points in his career. He and his apprentices functionally shared a household, which meant that it is not possible to say “this old book from somewhere on the Taliesin property was definitely a book that belonged to Frank Lloyd Wright” in the same way we can say that about items found in O’Keeffe’s book room.

Yet there are similarities. O’Keeffe and Wright achieved notoriety during their lifetimes and were acutely aware that followers and fans would be interested in the entourage of things—clothes, art supplies, books, furniture, cooking tools, receipts, and farm equipment—that were part of their lived experience. There is a prescience in how O’Keeffe and Wright anticipated and curated their legacies through their archives, either managing that process themselves or selecting people and institutions who would oversee their vast array of things posthumously.

It is an illusion, of course, that by touching a dress that O’Keeffe wore or a letter that Wright wrote, we can resurrect them or channel some aura of authentic and enduring personhood (I mean this in a Walter Benjamin way, not a New Age woo-woo way). But there were certainly times as I sat going through files at the Beinecke, at the Avery, in the O’Keeffe Museum Research Center, or among files at Taliesin West, where I felt somehow closer to Wright and O’Keeffe. I’ve heard other authors of monographs and biographies recount similar experiences, feeling some ineffable connection to the subject or in some cases even guided by them. I’m not a particularly spiritual person, but there is something undoubtedly sacred in the little notes we write to ourselves, the way we organize our spice drawers, the way we fold a shirt.

O’Keeffe meticulously kept records of her own artistic career and household business.