Wait, Frank and Georgia knew each other? And other FAQs

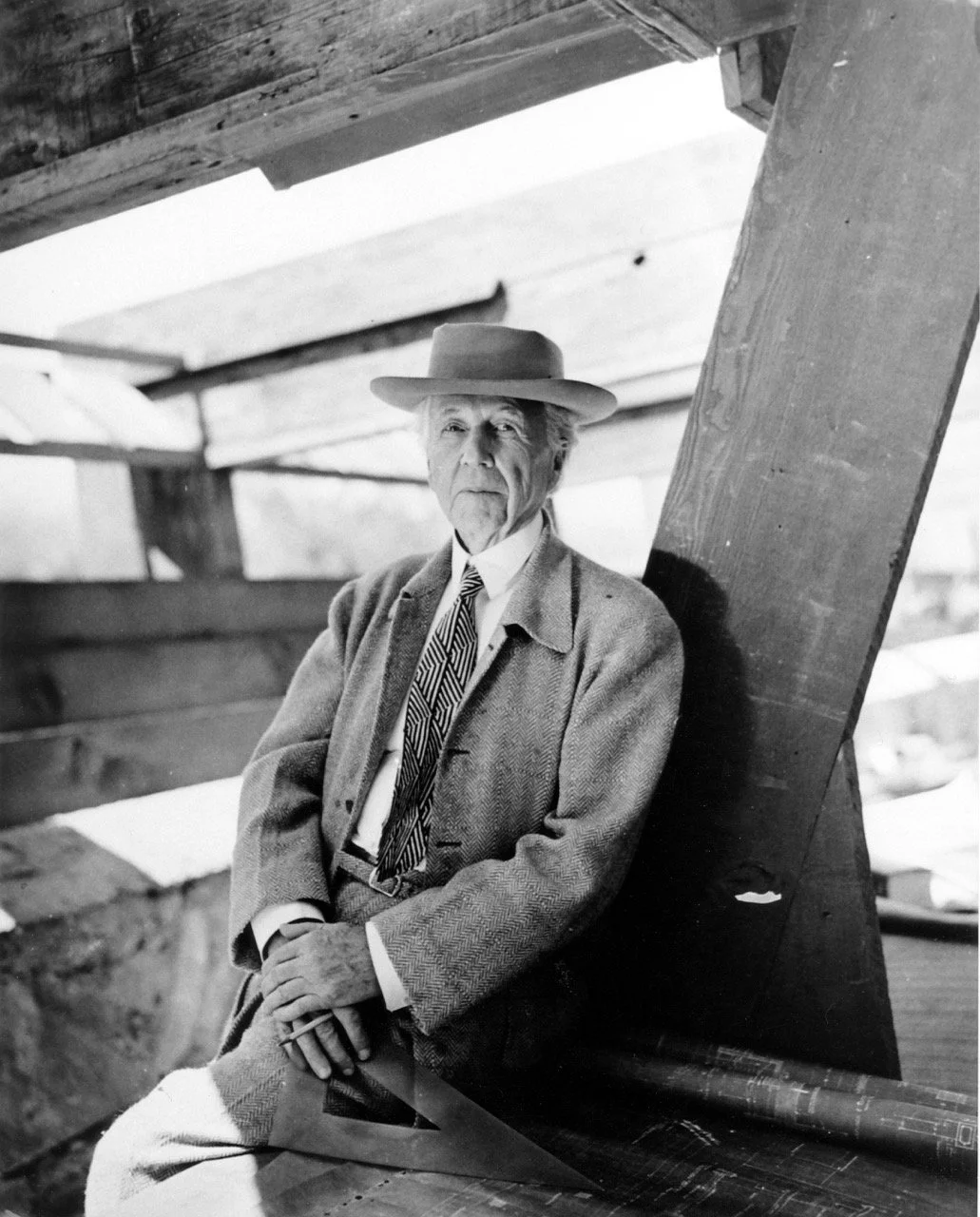

Ralph Crane. Frank Lloyd Wright in Taliesin West drafting room holding drafting triangle, Scottsdale, Arizona, March 14, 1946. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), 6006.00.

Alfred Stieglitz. Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918. Platinum print, 91/4 x 71/4 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. [2003.1.2]

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986). Untitled (Mt. Fuji), 1960. Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 1/2 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. [2006.5.354] Photo: Tim Nighswander /IMAGING4ART

A tiny, lovely detail from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Skyscraper Regulation (Chicago). Unbuilt project, 1926. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), 2603.001.

Pre-Order

Be among the first to receive a copy of Through the Long Desert when it ships on September 2, 2025!

Q: You wrote a book about Frank Lloyd Wright and Georgia O’Keeffe? Wait, did they know each other? [A pause, and then, often a little sheepishly] Did they date?

A: Yes! They did know each other…

The book works in part because Wright and O’Keeffe were friends and there are some really wonderful, poignant letters between them. O’Keeffe even gifted Wright a painting, which is something she very rarely did. It’s not like they were besties but they clearly respected each other’s work very sincerely and there was enough of an actual relationship there so that the book doesn’t have to rest on the formal resonances of their work alone.

As to the nature of their relationship, I am 99% sure their friendship was platonic. Both were partnered elsewhere and seldom in the same place long enough for sparks to ignite.

That said, there is certainly something romantic in their friendship. I’m using that word here in less of a twenty-first-century flowers & chocolates sense and more in a nineteenth-century gothic novel kind of way. They both clearly enjoyed the attention and respect of the other. They were attracted to the personal narrative that the other presented and the role they played in American cultural life. And then they expressed those things—emotively and forthrightly—in letters.

In writing this book, I became acutely aware of how pale and sanitized “friendship” as a concept has become in recent decades. Last year I read The Other Significant Others, which explores the possibility of recentering friendships and provides a history of how intense friendships were in previous eras of human history. The concept of romantic friendship, that friendship can be intense and even consuming without being sexual, has largely died out, a victim of early twentieth-century homophobia. Wright and O’Keeffe, like many others of their cultural milieu, maintained numerous romantic friendships, over the course of their artistic careers.

But part of the joy of doing this kind of historical work is that you can never be entirely certain; there’s no way to reconstruct the past with absolute clarity or precision. That ambiguity, I think, serves the structure and conceit of the book — the unknowns around their friendship allow us to ground ourselves more in what we can know, that is the work (painting & architecture) itself.

Q: Wait, your book is $65? Why is it $65? Is it like some kind of giant coffee table book?

A: I think people are afraid the term “coffee table book” feels derogatory…

That said, given the size of this book, yes, it is probably more at home on your coffee table rather than slung in your very hip shoulder bag for an impromptu café reading session. But I prefer to think of it as a visually lavish scholarly book.

Rizzoli (especially this particular imprint, Rizzoli Electa) is known for its lush, illustrated publications. This was originally meant to be a 30,000 word book. For context, a typically long-read article like you’d find in The New Yorker is usually about 10,000 words and my dissertation was a little over 100,000 words. At any rate, I turned in a manuscript that was almost 60,000 words. Rizzoli was blessedly chill about this but I still managed to cut back to 45,000 for what is a much cleaner, honed reading experience. There are about 200 images and many of them are printed full-bleed (right to the edge of the page) so the experience is very immersive.

Two other perks of big, lavish visuals for this particular project is that the colors on the O’Keeffes and the details on the Wright drawings are pretty jaw-dropping.

Some of the O’Keeffes have not been reproduced since the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Conservator, the brilliant Dale Kronkright, cleaned and restored them. Mt. Fuji (1960), just as one example, revealed itself to be a much more radiant, sumptuous shade of pink after restoration. And there were Wright drawings that I had seen in person at the Avery Library at Columbia University and thought I knew pretty well. But it was only after I got the proofs that I started to notice charming little details in them because the Rizzoli print quality is so crisp.

Q: Does the world really need another book about either Georgia O’Keeffe or Frank Lloyd Wright? Hasn’t everything that can be said about them already been said?

A: No one ever comes out and just asks me this question, but it’s frequently implied.

It’s a question that I asked myself a lot too during the early stages of the writing process. I think there are two things that make this book unique.

The first is the nature of the comparison. When art and architectural historians tend to write about two or more figures side-by-side, it’s usually because they were either romantically entangled or deeply enmeshed in the same movement. Wright and O’Keeffe are an interesting pair because they didn’t ever really compete or collaborate but they did provide each other with fuel and inspiration while operating at least comparable levels of fame. There are also a lot of (pulpy? sensational? archivally speculative?) takes on O’Keeffe’s and Wright’s respective personal lives. If you’re looking for murders, fires, and affairs, this is not really the vibe of the book. Nor is blind valorization and hero worship. O’Keeffe and Wright were only human, and I tried to portray them in all their messy humanity - brilliant, vulnerable, flawed, often quite funny, sometimes cripplingly self-conscious.

Second, the book is structured around all of the places that Wright and O’Keeffe shared and that informed each of their creative outputs: Wisconsin, Chicago, Japan, New York, and the American Southwest. Numerous other books have dealt with the role of place in Wright and O’Keeffe’s work, respectively, but usually as a one-off (O’Keeffe in Texas, Wright in Oak Park, etc.). Through the Long Desert tries to understand their approaches to landscape more holistically, positing that even though they were working across different mediums, they responded to similar kinds of stimuli in the places where they spent the majority of their careers. Each chapter feels a little different—the Chicago chapter, for instance, is more about an intellectual community and political orientation, than it is about the physical environment of turn-of-the-century Chicago. Each chapter has visual material and archival research never surfaced before. And even for these heavily-researched figures, when they are put into dialogue with one another, new ideas tend to bubble up.