Frank and Georgia Tell Me How to Write a Book

Ever felt like a ghost helped you write a book? The researchers behind a landmark Alexander Girard exhibition did — and I have to admit, I hoped for a little of that spectral magic myself.

Half expected to run into Mr. Wright on this cold March morning at Midway Barn.

“Like an aspiring nineteenth-century Spiritualist medium with an impending book project, I began to yearn to be likewise guided from beyond the veil.”

The wild patch of garden that I planted one morning in a fit of creative frustration.

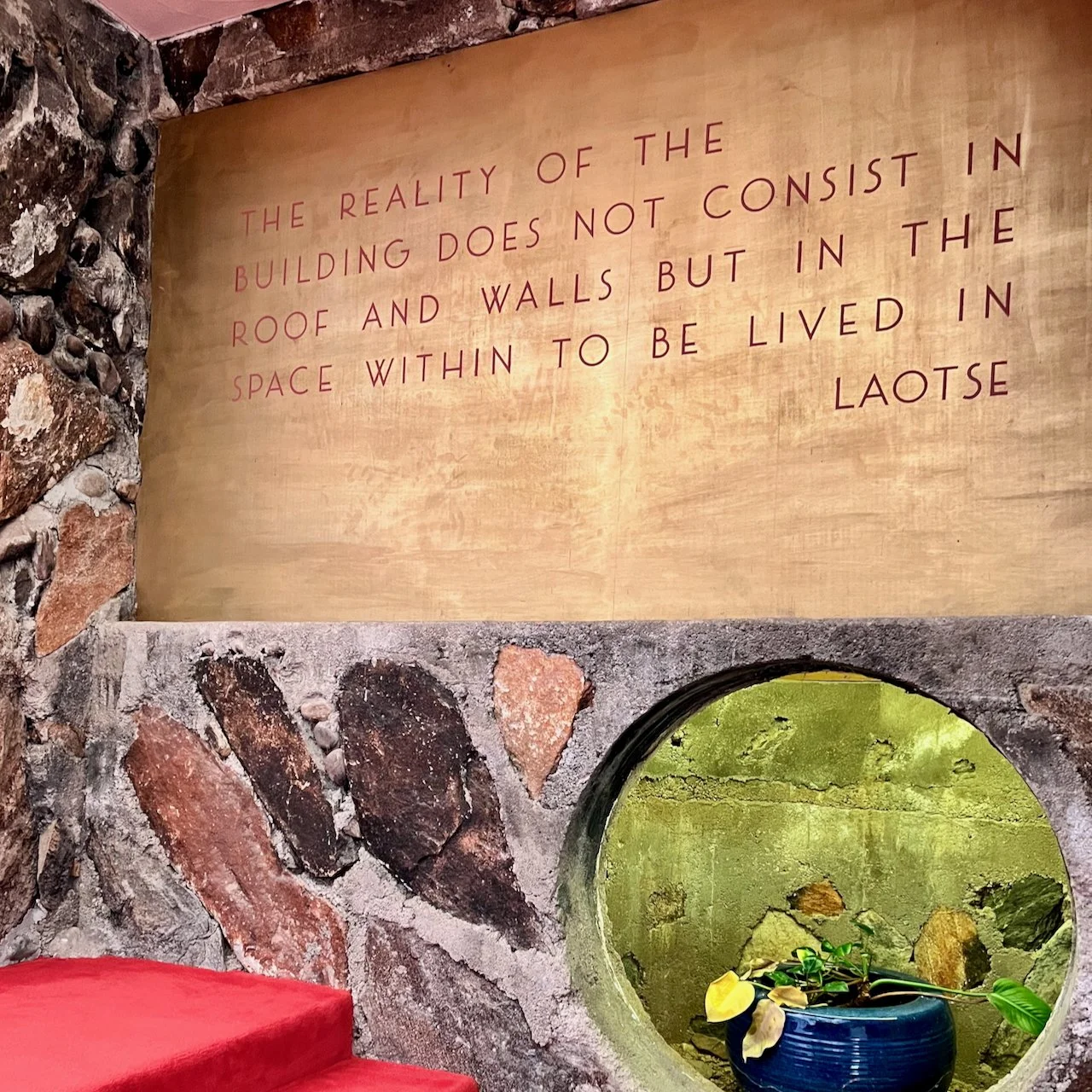

Paraphrased here from the Tao Te Ching, this idea is at the core of The Book of Tea, one of the first books written by a Japanese author in English about Japanese culture, aesthetics and philosophy. It meant so much to Wright that he put this quote on a wall in the Movements Pavilion at Taliesin West.

“I paint quickly because I know exactly what I want to do before I even stretch a canvas. Once I start, it’s simply a matter of getting my conception down exactly the way I want it.”

Several years ago, the Vitra Design Museum created a beautiful exhibition catalog to accompany the landmark show Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe. The authors, veteran researchers and academics, came together for a panel at the Museum of International Folk Art here in Santa Fe. With no small amount of incredulity and a touch of sheepishness, they confided that while writing the monograph, there were times when they felt the spirit of Girard palpably guiding the work. Like an aspiring nineteenth-century Spiritualist medium with an impending book project, I began to yearn to be likewise guided from beyond the veil.

Now, having completed Through the Long Desert, I can’t claim to be the recipient of any unambiguous visitations from Mr. Wright or Ms. O’Keeffe. Maybe I’m too much of a skeptic to warrant direct spectral guidance. But there were certainly moments in the process when the membrane between present and past felt more fungible, more permeable. It happened a few times walking the campuses at Taliesin or Taliesin West by myself at sunrise; that prickly sense at the base of my neck that I might turn a corner and run into Wright or one of the original apprentices. But more commonly, I would be reading something written by Wright or O’Keeffe and would find in their words the precise wisdom the moment required — the nugget that would reframe some conceptual difficulty or give me the strategies I needed to keep going when things got hard.

O’Keeffe and Wright were both prolific writers. O’Keeffe’s letters are wild, poetic, and sometimes wickedly wry meditations on creativity and everyday life. In her later years, she produced several books combining reproductions of her work with often cryptic meditations on her life and creative practice. Wright was also an avid letter writer, but he reworked and honed his ideas through innumerable articles and books. His autobiography — bizarrely written in the third person — weaves a rich if rather uneven narrative that speaks as much through its gaps and silences as it does through its tender and forthright confessions. I spent a lot of time with them through their words, circling back to those primary sources again and again.

Here’s what they told me:

Take frequent breaks, preferably to tend the garden.

Wright’s time on the farm with his uncles and aunts as a child became an anchor in what was often a destabilizing childhood. He would return to farming and gardening in later years, and even embedded agriculture as a core practice within the Taliesin Fellowship. Apprentices were expected not only to learn architectural design, but to participate in the cultivation of crops and animal husbandry that kept the Fellowship fed. O’Keeffe brought with her from Wisconsin a love of gardening that followed her through the rest of her life. The desire to have a garden is largely what spurred her to pursue a second house in northern New Mexico. Unlike the remote home the painter purchased at Ghost Ranch in 1939, the house at Abiquiu was located on a local acequia (or irrigation ditch) and came with water rights. Planting and cultivating fruits and vegetables allowed her to avoid frequent trips to Española or Santa Fe for groceries. Decades before “organic gardening” and “plant-based diets” were in the mainstream vocabulary, O’Keeffe gravitated to these ideas instinctively.

Struggling with an early draft of the book manuscript one morning, I took a page from Mr. Wright and Ms. O’Keeffe and busted out the electric rototiller to break up a recalcitrant patch of rocky clay in my front yard. After I finished amending the soil, I loaded my Subaru up with gallon and five-gallon starts from Plants of the Southwest and turned that corner into a little oasis of native flowers and trees. There may be more cost-effective ways to counter writer’s block, but my afternoon of fevered planting in 2023 paid off. That original eclectic selection of seedlings has grown into a robust grove — the backdrop for this year’s wild tangle of beans, sunflowers, and pumpkins. Whatever snarl of ideas in which I’d ensnared myself dissolved amidst the sweat and the soil and the afternoon sun.

Read voraciously.

O’Keeffe’s book room at her Abiquiu house contains over 3,000 volumes. Wright’s library is a little trickier; the constant stream of apprentices through Taliesin and Taliesin West makes it more difficult to tell, decades later, which books were actually Wright’s. But Wright talks about books in his own letters and in the texts he wrote about what influenced his work. I spent a lot of time doing background reading in the early stages of this book. I read the big, canonical biographies of Wright and O’Keeffe, of course, but I also tried to read what they read — the books that influenced and inspired them. Though Wright could be, well, touchy about admitting the influence of other architectural designs on his work, he was much more open about ideas gleaned from other media: dance, theater, Japanese woodblock prints, and literature. O’Keeffe’s letters are likewise full of references to her current reading and what had moved her. I often read O’Keeffe’s actual copies at the Research Center at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and could see what she underlined. Some of those underlined passages are quoted in Through the Long Desert.

There was certainly lots of overlap in their libraries, but one book that spurred them both to new late-career experimentation was The Book of Tea by Okakura Kakuzō. It became a lodestone in my text as well. If you haven’t read it and are nursing an interest in Zen philosophy or aesthetics, do yourself the favor of picking up an inexpensive paperback copy.

Give ideas generous time to germinate before trying to produce something.

O’Keeffe and Wright were both notoriously fast workers; once they started on a design or painting, the final product usually developed quickly. Wright often bragged, “I just shake the buildings out of my sleeves.” The speed of their actual execution, however, was the result of a great deal of mental pre-work. As O’Keeffe explained, “I paint quickly because I know exactly what I want to do before I even stretch a canvas. Once I start, it’s simply a matter of getting my conception down exactly the way I want it.”

I had a lot of time to think about the shape of this book before I actually started writing. At the end of my research fellowship at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in late 2019, I produced two competing outlines: one about place and landscape and the other about the formal similarities in Wright’s and O’Keeffe’s work. I worried that the first formulation was too reductive, maybe too oriented to a popular audience, and that the formalism of the second version would be too esoteric and academic for many readers. The O’Keeffe Museum and Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation urged me to marry the two, keeping the most compelling ideas from both. I felt stuck on this advice with no clear way to resolve the tension — and then the pandemic happened. Suddenly publishing slowed to a crawl and supply chain issues delayed projects in the pipeline. I went from not knowing how to write this book to not knowing whether I’d have a book to write at all. But during those years I kept mulling the project, turning it over in my mind. I wrote and rewrote my initial outlines, started tentative chapter drafts, and ordered more and more books. When I finally got my contract and started writing in earnest in 2023, I can’t claim that I just “shook the book out of my sleeves,” but it did go surprisingly quickly. I stumbled around with the Wisconsin chapter for a few months, but then hit my stride and the rest of the chapters fell into place by my draft deadline in November.

Other lessons from Frank and Georgia that I’ve tried to take to heart:

You never regret going for a walk.

Develop a unique sartorial style, and maybe even sew your own clothes.

Adopt a rather niche exercise regimen.

Don’t discount the powers of retail therapy.

Invest in a good sound system (or good instruments, if you play).

Use travel to reset your attunement to beauty.

Want to hear about any of these in a future newsletter? Drop me a line!