Body Chapters: Burnout and Book Tour

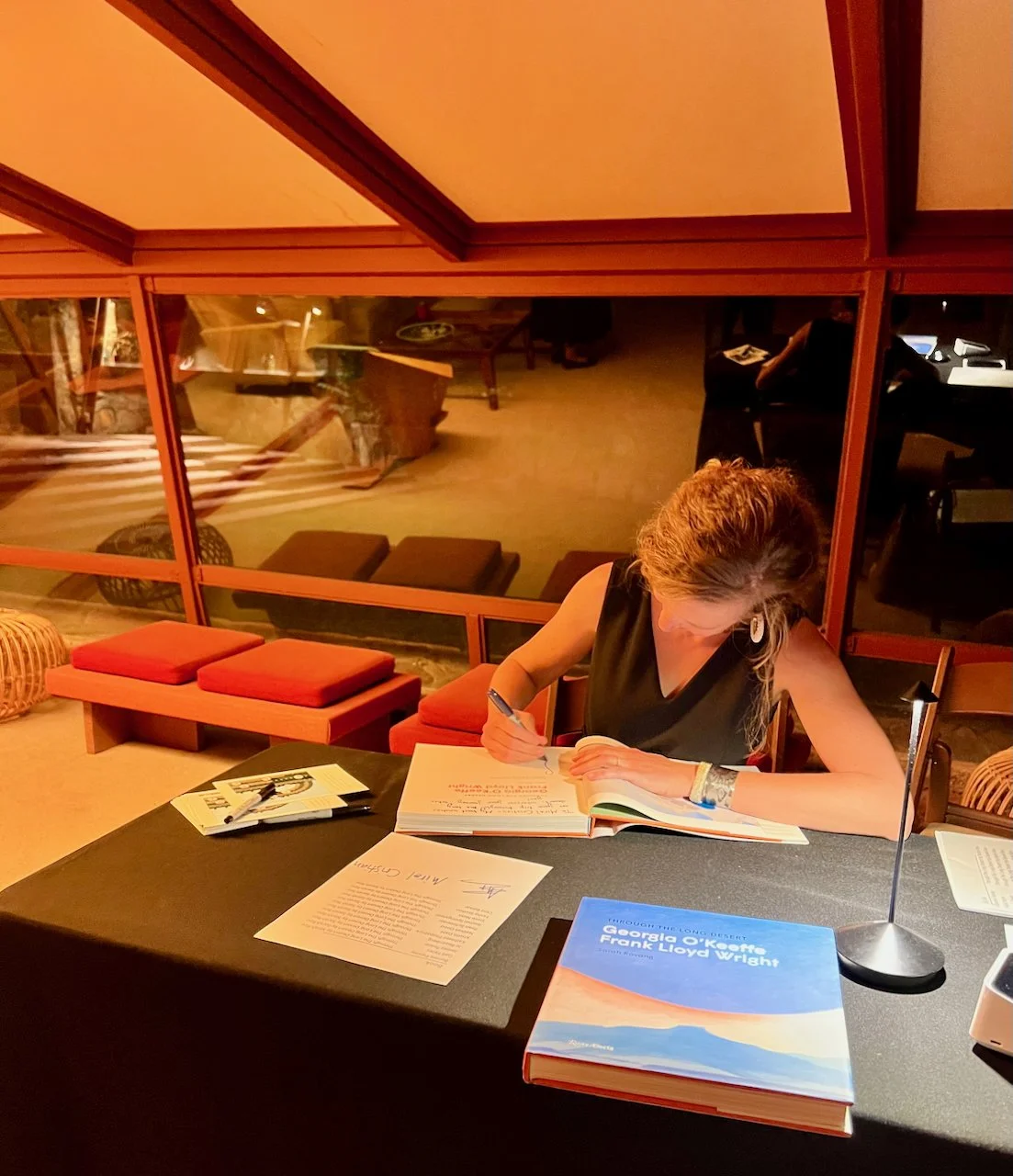

After wrapping up my midwest mini-tour (three states, three talks, three days), I had about ten days at home before getting in the car and driving to Taliesin West. I spent eight days in Arizona doing book stuff at Taliesin West, squeezing in a family vacation, and attending a marathon 48-hour conference for my day job. I got home on Thursday, and then on Saturday gave a talk at a charming indie bookstore in Albuquerque. Somewhere in there Halloween happened, featuring not one but two homemade costumes for my four-year-old daughter (the late Santa Fe-based designer Alexander Girard and a witch).

I had been planning to leave this Sunday for Providence and some events at Brown, but then my body gave out. Last Friday, having gotten home at 8 pm the night before, I went into the office like the good little government worker I am and almost immediately started having chest pain. I am pretty sure it was indigestion plus muscle cramps plus reacclimatizing to the altitude in Santa Fe, and I haven’t had a recurrence. I don’t feel anxious or brain foggy or even “stressed” in the typical American workaholic way, but I do feel run down, strung out, and existentially exhausted. But getting back to Olympic lifting this week, even with a much easier program than usual, has made it feel somehow bearable; just to feel power and delicious soreness in all the muscle groups that have been hunched, cramped, stagnant, and neglected over the past month.

Understandably, I’ve been thinking a lot about the body recently. In early versions of my manuscript, I was planning to have a whole section on O’Keeffe, Wright, and the body. It was going to deal with illness and the fragility of the body, but also with movement, exercise, and dance. Ultimately, I couldn’t find a place for it and ended up just keeping fragments of the original ideas in the chapters where they made sense. There’s a section on Wright’s theater designs and how that work informs the way the Guggenheim orchestrates encounters with art through architectural cues. And the portion on O’Keeffe in Texas is very much about the body — the young artist is living and teaching in the Panhandle and having a deeply embodied experience of the plains. She’s camping, hiking, painting en plein air. Plus, she’s dating a full lineup of local men (some of them married) and then writing to Alfred Stieglitz (also married) about all of it. She’s painting abstract nudes of herself and romping around her rental house in a kimono and generally scandalizing her conservative neighbors. There are some absolutely sizzling lines in this section: “I feel rough like the wind tonight. I’d like to take hold of you and handle you rather roughly—because I like you.” (That’s O’Keeffe to Stieglitz in 1916—just trying to get my book to a PG-13 rating here!)

But in writing the section on the body, I also kept running into this issue that O’Keeffe and Wright clearly had very different understandings of their own embodied experiences of the world, and their creative positionality as mortal, corporeal beings. To put it more bluntly, O’Keeffe is a lot more comfortable engaging with sex and death than Wright. O’Keeffe had this really complicated relationship with sickness, especially tuberculosis, which took the lives of several uncles and eventually her mother. O’Keeffe herself had a number of serious illnesses and significant medical procedures. She’s also very comfortable with her own sexuality. Say what you want about her flower paintings (I frankly think there are more interesting questions to ask about O’Keeffe), O’Keeffe is a child of the early twentieth-century avant garde. Stieglitz’s nude portraits of her are (in)famous but O’Keeffe had painted plenty of nude self-portraits years before disrobed in front of his camera. In later life, she’s into niche exercise regimens, bodywork, and organic cooking long before any of those things are in the American mainstream. Her letters are filled with reflections on the operations and rhythms of her own body.

Wright on the other hand… well he’s born in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and in some ways is a Victorian at heart. Though his maternal clan is spiritually and politically progressive, that doesn’t necessarily translate to sexual mores. Wright’s architecture is organic but I wouldn’t describe it as bodily, if that makes sense. For all his rootedness in nature and landscape, and his valorization of manual labor, Wright’s work doesn’t hit the same lizard-brain/phenomenological buttons as some of his contemporaries. Don’t get me wrong, Wright’s very good at controlling movement and orchestrating physiological reactions. But his device of compression and release is a little different from wanting to run your hands over the walls or lay down on the floor. I find Wright’s architecture deeply soothing, though rarely seductive. For all of his unconventional tendencies and his destruction of the Victorian box-as-house, there is something remains something maybe a bit puritanical in his architecture, though he gets more sensual as his career evolves. I think part of that evolution is the influence of his third wife, Olgivanna. Olgivanna started her career as a dancer and student of George Gurdjieff, a Russian-born philosopher and mystic who developed a series of “movements” designed to synchronize the spirit and the body.

Taliesin West, which became the home that Olgivanna most identified with, reflects that interest. There are not only multiple theaters, but the campus itself invites a kind of fluid, improvisational movement. It’s less structured, less formal, than Taliesin. When I stay there, I find myself compelled to wander without a clear objective, spiraling outward from the main campus and onto the winding footpaths that lead to the student shelter zone where half-forgotten desert experiments offer a glimpse into the student life and design pedagogy of decades past. Amidst the saguaros and deceptively cuddly teddy bear chollas, these shelters appear at dawn and dusk as a fleet of delicate spaceships in the raking light. On my last morning, I’ve hiked Sunrise Peak and clambered around the Taliesin West campus. My legs are sore and aching from the exertion, though I am loathe to leave. I pull myself into one of the shelters, a simple wood platform with a roof, and just watch the desert do its dance for a few last precious minutes.

And now I’m home. I’m watching the November super moon set out of one window while the sun rises in the other. All is poised and quiet, but I’m feeling rough like the wind this morning. If you are too, I hope you can find a little stillness and silence in your body. Watch that great lunar orb set in the western sky. Join me for a second cup of coffee and spend a few moments doing absolutely nothing before the demands of the day start gnawing on the edges of your consciousness. This sweet and fleeting stillness won’t last long.

All that hunching during book signings probably hasn’t helped.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986). Nude Series XII, 1917. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 177/8 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. Gift of the Burnett Foundation and the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

Finding shelter and a quiet place to rest at Taliesin West.